Read about Maureen Fitzpatrick’s experience with her daughter’s addiction to heroin and how they were able to battle and overcome the deadly disease.

Meet Maureen

Not too long ago, Maureen Fitzpatrick cowered in the corner of her New Jersey home, hoping her heroin-addicted teenage daughter wouldn’t fulfill the threat to slit her mother’s throat as she shattered glass candles around her.

Today, Maureen stands tall when she talks about her family’s struggle with her daughter’s addiction. She’s found poetry as a form of self-expression that helped her cope with her daughter’s heroin addiction. She is now inspiring other parents to do the same.

A Mother’s Horror

Maureen could tell something was wrong with her oldest daughter, Erin, when the star athlete and respectful child she knew grew into a negative, oppositional and violent teenager.

Alarmed by the transformation, Maureen and her husband desperately tried to find an answer to the mysterious change, even going so far as to take Erin to the hospital in search of an underlying mental disorder. Although the tests came back positive for drugs, health privacy laws protected Erin and her wishes to keep the secret from her parents. Maureen and John remained in the dark.

The idea of Erin doing drugs had crossed Maureen’s mind. She was a teenager, after all, and Maureen had noticed the smell of marijuana on her daughter a time or two. But even her worst thought — that Erin was doing Oxycontin — paled in comparison to reality.

One day Maureen saw Erin and a friend shooting up heroin in their home. It’s a moment she’ll never forget.

“It was a terrible ‘aha’ moment,” Maureen recalled. “It was devastating. When I saw her shooting up, my heart dropped.”

With her secret out, Erin’s behavior only got worse. She grew increasingly violent. The consequences of addiction were daily occurrences — screaming, yelling, throwing objects, breaking things, threatening her parents and four younger siblings, and even calling the police for help.

I became so many emotions at once — panicked, shocked, scared — you can’t even imagine.

The family vehicle served as a getaway car on many occasions, shuttling the terrified troupe to safety. One such outburst was so upsetting, Maureen’s son began vomiting in the car as she drove them away from their family home. Other times the children took refuge in their bedrooms as Maureen called law enforcement for help.

Erin was just a teenager — 15 years old — when she started using drugs. And until she moved out of her childhood home at age 22, to Maureen, the drug abuse made the Fitzpatrick home felt like the epicenter of chaos in Pitman, New Jersey.

“My four other children are still affected today,” she says. “They are still learning to forgive her. A lot of their childhood was taken away from them because she did heroin.”

Finding Help

Maureen and John turned to everyone they could think of for help — police, teachers, acquaintances, and friends who worked at the hospital or in drug rehab services.

They quickly found the law shielded Erin and, in a way, fueled her addiction.

Hospitals kept her records private and released her after only a few days, and rehab facilities wouldn’t take Erin unless she was willing to commit to recovery.

It didn’t matter that she was 16, they still wouldn’t take her. Her addiction kept spiraling out of control.

Other times, Erin would agree to rehab but would leave shortly thereafter and quickly relapse. It wasn’t until she had been put in jail at 22 that Erin decided enough was enough. She and her boyfriend moved across the country and she began her recovery.

Now, two years into aftercare, Erin is still sober and working to repair her relationship with her family.

Maureen is also working on repairs.

Maureen found poetry as a release during the most tumultuous years of Erin’s addiction. We asked her about her daughter’s recovery and how her own poetry helps inspire other parents enduring similar experiences.

Q: How did you use poetry and other strategies to cope with Erin’s addiction?

The poetry came later after things started to calm down. Honestly, though, my way of coping through the worst of it was knowing that I had to get up and take care of my other children. Knowing I had to get up and go to work.

The disease was so strong and so heavy on everyone’s shoulders, even getting out of bed was a challenge. Thank God I had other children I had to take care of. I think I would have been destroyed without that.

Everything was chaos — with her addiction and her violence, every single day was a crisis. She was missing, she was jumping out of cars — every single day was chaos. I was so shaken, I used to try to get rid of the pain by sleeping it off. I had no choice, I was so traumatized by it all.

Q: How did you find poetry as your release?

I had tried to do some meetings, people say go to Narcotics Anonymous or Families Anonymous, but I didn’t find it helped me. It just reminded me more of my daughter’s illness.

I saw another approach to heal, though. I had some friends that write and they said, “Why don’t you start writing?” I taught reading and writing in school so I started writing poetry. There is a huge writing community on Instagram, believe it or not, so I turned there and started posting my poems.

People were encouraged by it, and I found it very healing for me. It allowed me an outlet to pour everything down on paper. I didn’t care if I was swearing, I didn’t care if I was wrong, I wrote it all down. I wrote about 3,000 poems in the last three or four years of her addiction, and I found when people read it they related.

I decided to write a book because a publisher had recognized my work on Instagram and asked me to send them material. I did and they said it’s something they would like to publish.

Everybody thinks Instagram is just pictures, but there is a big poetry community on Instagram. If you look up #poetry, you’ll see it’s like a community, we share our stories and encourage each other. A lot of poetry is very raw and real, very emotional.

Q: What addiction recovery organizations do you support?

The proceeds from my book are donated to services that try to prevent addiction in my community because I didn’t want to make money off of this. One is the Kids Caring Foundation, which is based in Pitman and tries to get educational services on addiction. Kids Caring also encourages positive behavior. They planted a “say no to drugs” garden, collected clothes for the homeless — all positive activities.

I also work with two other groups. One is Stand Up To Addiction, which was started by a man in our community to raise money that helps families of addicts, like buying gas cards or flying a family member to rehab in Florida. I also partner with the Southwest Council in South Jersey, and the money raised for them will be used for recovery resource services. We hope to grow that money — the idea is to take the money I give them from the book and create an event like a 5K to do some more fundraising and grow the funds.

Q: What advice do you have for parents going through this experience?

You have to continue to love your child even when you feel you can’t. Remember to hate the disease, not the person who has the disease. And sometimes love looks like a turned back, sometimes you have to walk away with love and say, “It’s up to you now to get better.”

I found the best thing for me that allowed me to heal and allowed my daughter to start healing was that I forgave her. I had so much anger, and even hatred because it was seven years of hell, but when I forgave her and I told her I forgave her, she started to heal and I started to heal. She realized it wasn’t her fault. When I forgave her, she was able to start healing and I was able to start healing, and I felt such a weight lifted.

There is hope.

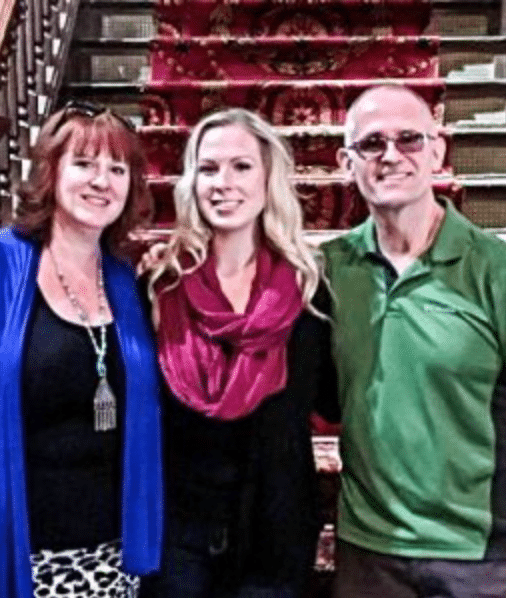

Maureen Fitzpatrick is a teacher, wife, mother of five, and published poet from Pitman, New Jersey. In March 2016, she released her first book of poetry, Beyond Horizon Fall. The narrative takes the reader through Maureen’s experience trying to parent a teenage heroin addict, one poem at a time. The collection runs the gamut of raw emotions — including uncertainty, despair, grief, and hope — with the goal of showing other parents in similar situations that they are not alone.

The Recovery Village aims to improve the quality of life for people struggling with substance use or mental health disorder with fact-based content about the nature of behavioral health conditions, treatment options and their related outcomes. We publish material that is researched, cited, edited and reviewed by licensed medical professionals. The information we provide is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It should not be used in place of the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare providers.